As a tokusatsu junkie and a manga fiend, people sometimes ask me – “Who’s your favorite mangaka for henshin heroes?” They’ll usually accompany that with some suggestions: Shotaro Ishinomori (the King of Manga and creator of Kamen Rider), Go Nagai (Ishinomori’s prolific protégée who reshaped the genre on multiple fronts), or even Yoshiki Takaya (whose Guyver manga made quite the impact in the US back in the day). I love those guys, but there’s a single name who tops my list… Masakazu Katsura.

At this point, the person who asked the original question will usually blink a few times, ask me to repeat myself, and then utter, verbatim, the following: “You mean the guy who draws the butts?”

This isn’t really fair. On balance, *all* of them draw butts:

But I get their point. There’s something special about Katsura butts, an unparalleled, loving craftsmanship that’s so renowned that he literally gives ass-drawing lessons. He’s basically the Leonardo da Vinci of manga posteriors.

I digress. This is, after all, not a site for cartoon T&A, but one for the discussion of Japanese superheroes. Assuming I haven’t already gotten you into too much trouble with your boss, let’s delve into a little of what all this Katsura dude has contributed to that genre! (Spoiler warning…there may be more butts.)

Unlike many artists who grew up obsessing over their favorite manga, Masakazu Katsura was always more of a tokusatsu kid, idolizing Ultraman, Metal Heroes, and Super Sentai. He went to a school festival dressed as Goggle V’s red ranger, and even participated in a Sun Vulcan fan film, so, when he started doing manga at the age of 17, it’s no surprise that it had that flair. His first short story, Tsubasa, featured a winged android hero that would prove very much a prototype for his later mega hit Dream Warrior Wingman. Though unpublished, it got an honorable mention in the Tezuka Prizes in 1980, and paved the way for Katsura to get his first publication, in the prestigious Weekly Shonen Jump, no less! That professional debut, Tenkousei wa Hensousei, would be the other genre for which Katsura became famous (sexy comedies), though even there he included an extensive scene where the characters go on a date to see a movie about the Ultraman villain Baltan. Needless to say, he wasted little time jumping back to superheroes, with the 1981 two-parter Gakuenbutai 3 Parokan, which is basically a schoolgirl spoof of Sun Vulcan.

This all set the stage for one of Katsura’s most enduring successes: the 1983 series Dream Warrior Wingman. It was a smash hit, running 13 volumes, getting an anime TV series from Toei, and even getting translated for international distribution around the world (English-speaking territories excluded; d’oh!). The series is a classic, and even decades later, Wingman is, more than any other Katsura work, nearly always included in any rundown of the most iconic Shonen Jump titles or characters. Just play “Where’s Waldo” with that pointy blue helmet:

So, what makes Wingman so good? Well, on top of being a solid mix of action, romance, and comedy, it was groundbreaking as one of the earliest otaku-centric series of the 1980s. Kenta, the main character, was, like Katsura himself, a major henshin hero fanboy; it’s easy to forget in this age of titles like Akibaranger and Samurai Flamenco that this sort of trope wasn’t always so common. The story kicks off when Kenta meets a girl carrying a “dream note”, which has the power to change reality (yes, much like a certain later ultra-popular Shonen Jump property, this hinges on a magical notebook). Kenta puts his original superhero character into the book, and faster than you can say “Beetleborgs stole this premise” he’s defending a parallel universe from an evil dictator.

I’m honestly shocked how under-the-radar this series has managed to stay with English-speaking fandom; despite the general significance in Japan, iconic design work, and memorable characters, only a couple of volumes of the manga have even been fan translated, and one one episode fansubbed. I imagine a show like this would be a no-brainer for Discotek or someone similar to pick up, so I’ve got to imagine that some sort of rights quagmire must be holding it up. (Fun trivia: the voice of Kenta in the anime was then-new actor Ryo Horikawa, who’d go on to iconic roles such as Dragon Ball Z’s Vegeta and Saint Seiya’s Andromeda Shun. Also, Katsura’s assistant on Wingman, Yoshihiro Kuroiwa, went on to a career at Jump with his own henshin hero, Zenki.)

It’s also worth noting that Katsura became quite ill towards the end of Wingman’s run, and spent a long while afterwards recovering in a hospital. During this time, he says that he re-taught himself to draw, which is obvious when you see the dramatic shift in his art style following the incident. Katsura’s initial art style, somewhat typical of the era, doesn’t stand out a whole lot, but his later look is unmistakably striking.

It’s also fun to mention that Wingman briefly appeared in live-action for a cameo in the 1991 Video Girl Ai movie as a show-within-a-show. This Wingman was actually played by Katsura himself! (While we won’t talk much about that title here, Video Girl Ai is quite a fitting match for Wingman, as Katsura’s other most iconic opus. It, too, centers around the idea of making an otaku fantasy a reality, as its concept is that a dateless loser rents a videotape of a cute girl, but then the subject of the tape pops out of his TV screen and starts living with him. It’s basically a romantic comedy version of The Ring, and one has to wonder if Katsura was inspired by the same urban legend as Koji Suzuki, or if the legend was inspired by Video Girl Ai. A chapter of Oh My Goddess was doing the same thing at around the same time, too.)

Following Wingman, Katsura did a giant hero short titled Voguman that’s very Ultraman-ish, and the two-volume series Super Mobile Troop Vander, which is sort of a Metal Hero in which the title character is formed by the two protagonists kissing. Fusing heroes is an old trope in henshin heroes from works like Barom 1 and Ultraman Ace, so it makes sense that it was actually the fanboy Katsura who suggested that Akira Toriyama incorporate the fusion mechanic into Dragon Ball later.

Next, Katsura briefly tried his hand at magical girls with Pantenon, which is about a superheroine who transforms by removing her panties, which, needless to say, didn’t really “take off” (that was her henshin phrase). After that he began to focus more on romantic works for a while, including Video Girl Ai and Present from Lemon, but it was actually another magical girl who brought him back into the superhero game: Shadow Lady.

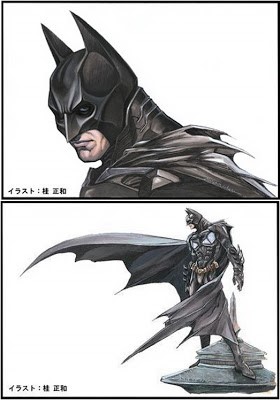

See, one thing that happened in the interim is Tim Burton’s Batman, which is a favorite of Katsura’s (even though he admits it isn’t very good). He became a Bat-maniac, making fan-art, designing action figures, even inserting Batman expies into scenes in Video Girl Ai and I”s (which is my all-time favorite manga, BTW, a romantic drama in which the best girl briefly works as a special effects technician, hence Batman). This resulted in a palpable chiropteran influence on his next couple of heroes, Shadow Lady and Zetman.

Shadow Lady actually went through a few iterations, first as a short five-chapter story in 1992 (in full color, like our beloved American superhero books!), then rebooted for a short in 1995, before finally becoming the three-volume serial the same year (available in the US from Dark Horse). Each version centers on a girl named Aimi who transforms using eye shadow into a phantom thief, and, like Rainbowman, different colors of eyeshadow result in different forms and power sets (a trope that’s only become more common in TV heroes over the years). Each transformation is associated with different animal forms (bird, cat, rabbit), but it’s the final version of the manga that gives her the bat motif, with the last name “Komori” (bat), a base form that’s black and winged, and a cute power-granting mascot (a staple of magical girls) named Demo.

On the other hand, the original manga had a character named Technoman who pretty much skirted the Batman design to the point of potential infringement. Both versions are well-worth checking out, as they surprisingly don’t cover a lot of the same territory, and the ideas were really reimagined from incarnation to incarnation.

Another series with aspirations of quasi-demonic Batman and a circuitous publication history is actually Katsura’s magnum opus: Zetman. Originally a 49-page story published in 1994, Zetman got serialized in 2002 for a sprawling 20-volume, 12 year run (not including the Alphas spin-off novel by Hideyuki Furuhashi). It’s a manga that really should have been picked up by a US licensor by now, but sadly the anime adaptation was mediocre and a lot of licensing is based on preexisting interest in adaptations. Plus, it’s hella grimdark, so Viz’s Shonen Jump line would probably avoid it like the plague.

Zetman hinges around the interaction of two opposing superheroes, the street-urchin escaped science experiment Jin (the titular Zet), and the privileged Kouga (who goes by Alphas). They’re foils: light and dark, rich and poor, mechanical and organic, each with different moral convictions informed by their backgrounds (and different familial tragedies). It’s edgy and violent, unlike Katsura’s other works, and as you can guess from the character designs, heavily influenced by another hero of which Katsura is a fan: Devilman.

Zetman has tremendous design work on display, as several other creators of similar mindsets contributed their own creature, character, and mechanical designs to the work, including Yasushi Nirasawa (Kamen Rider Kabuto), Katsuya Terada (Blood the Last Vampire), Takayuki Takeya (pretty much every Keita Amemiya project), and, of course, Akira Toriyama. Yes, *that* Akira Toriyama.

Katsura and Toriyama met through their mutual Shonen Jump editor Kazuhiko Torishima, and the Fukui native Katsura quickly bonded with the Nagoya native Toriyama over being boonies folks in the land of Tokyoites. It’s interesting reading transcripts of the two interacting; they constantly rip on each other in a manner much like competitive characters in a Jump comic might. Toriyama has even gone so far as to proclaim Katsura the only man he considers a rival, which frankly says a lot, coming from the creator of arguably the most significant popular manga ever. I’m sure it’s in good fun, considering how often the pair do fan art of each other’s works:

They’ve also collaborated quite a bit. Their first joint manga was the short story Sachie-chan Good, in which a martial artist and ninja schoolgirl are recruited into a galactic patrol to fight aliens (the most manga premise ever?). This one got an extremely limited US release, sent out to Shonen Jump Alpha subscribers and at New York Comic Con; whenever I see someone who works for Viz I pester them for a proper reprint. After that, the duo made the 2009 three-chapter series Jiya, about a very Ultraman-ish galactic patrolman who fuses with a human and defends the earth, foreshadowing Toriyama’s later Dragon Ball prequel series Jaco the Galactic Patrolman. Since it appears to be the same continuity, it’s shocking that Viz hasn’t jumped on Jiya yet, but I could also understand concerns over it as a seinen work, scandalizing young Dragon Ball readers with its fellatio jokes and whatnot.

Toriyama and Katsura also both worked on the smutty artbook Bitch’s Life (a Yasushi Nirasawa-edited anthology which included Katsuya Terada, Tsutomu Nihei, Range Murata, and more), but let’s just not talk about that. (Furthermore, the duo announced another collaboration in 2015, but no further details have manifested since.)

Katsura even dipped his pen into the field of spoofing Toriyama a little with his 1993 5-volume hit DNA2. That one’s an action rom-com in which Karin, a time-traveling agent from the future, is sent to prevent 21st century overpopulation caused by the genetic lineage of a highly fertile “Mega Playboy”, who, at the time she reaches, is still just the puking teenage loser Junta. Of course, Karin’s attempts to rewrite Junta’s DNA actually trigger the Mega Playboy gene, which gives him a full-on Dragon Ball-ish transformation sequence. This all culminates with a climactic battle against school bully Ryuji, who steals the DNA-altering tech to make himself superhuman, and, surprise, wears what looks like a Batman mask. The DNA2 manga never got a US release, but the anime has, and it’s a very faithful adaptation.

Another long-time collaborator of Katsura’s is the tokusatsu director extraordinaire Keita Amemiya. The two attended vocational school together (along with Katsuya Terada and Takeyuki Takeya), and Katsura has a walk-on role in Amemiya’s 1991 classic alien bounty-hunter flick Zeiram. When Zeiram was successful enough to warrant a sequel and animated prequel (Iria: Zeiram the Animation), Katsura did the character designs, adapting Yuko Moriyama’s look from the original:

Iria’s look seems like quite the influence on Karin from DNA2, doesn’t it?

There’s even art Katsura did of her with blue streaks in her hair, like in the live-action films.

For many years, Zeiram appeared to be Amemiya’s magnum opus, but fans from the past decade or so would be far more familiar with Garo, which is sort of like if Iria was a dude who hunts demons instead of aliens, and had a talking ring instead of a talking wristwatch. Katsura has a cameo in the tenth episode of 2014’s Makai no Hana, the fourth Garo season, and has a major voice acting role in the first animated series Honoh no Kokuin right afterward (he was the guy with the glasses who builds the mecha-Garo). Of course, he’s most associated for doing the character designs for the second animated series, Crimson Moon. While it’s not the best season of Garo, Katsura’s character designs are boss. That Garo anime takes place way back in the Heian era (hence lots of cultural baggage that tends to trip westerners up), so for the record, that’s two different anime prequels to Amemiya tokusatsu that he drew for.

Amemiya has returned the favor with the occasional piece of fan-art, such as this Shadow Lady sketch, along with all the cameos.

It’s also worth noting that since both guys worked with Takayuki Takeya, it’s little surprise that Katsura did some creature designs for Kamen Rider Drive, as well.

However, for more recent anime fans, there’s one mega hit with Katsura’s name attached that we haven’t gotten to yet: Tiger & Bunny. This Sunrise-original anime series is set in a world where superheroes are commonplace, and follows a group of top heroes on their reality TV show… I have few words to convey just how great Tiger & Bunny is, just watch it. On top of designing all of the characters, including Ultraman-like glowing aesthetics to the two main character heroes with time limits, Katsura did do a handful of manga shorts for the series. The main manga adaptation is by Mizuki Sakakibara though; caveat emptor if you’re only looking for Katsura’s stuff.

Tiger & Bunny was a smash hit when it aired seven years ago, so of course it’s only now that Sunrise is getting around to new content (a movie and a half aside), with Double Decker. A buddy cop show in a world with super-powered people, it’s more of a spiritual successor to Tiger & Bunny than a direct tie-in, but it still has the kinetic action, sci-fi gizmos, ambiguous sexuality, and, of course, gorgeous character designs.

It’s been a great year for Masakazu Katsura fans overall, with a new TV drama sequel to Video Girl Ai, the currently airing The Girl in Twilight (based on the mobile game), and last month’s TV movie Plastic Smile (about a cosplaying woman who works for a plastic model company, keeping the otaku interests close). As superb as his design work is, though, what I really love is his manga composition, with stellar pacing and some of the most emotionally-charged artwork you’ll ever see on a manga page. Hopefully he’ll return to that sort of work in the future (I can understand the hiatus after the grueling job that Zetman must have been), and fingers crossed more of it gets translated for a wider audience. I heartily recommend giving one of his manga a read, even the non-hero stories. The man can do amazing character work and compelling drama…and, if that’s not enough for you, there’s always…. well, y’know:

It is simply an aquired fine taste to appreciate the booty and all great round things it brings to our life

Amen

Pingback: A look into Astral Chain - Stinger Magazine

Pingback: A Decade Under the Influence…of Anime: 2012 | GONZO.MOE