Have you ever wondered about how the Death Note anime started during the short four-month window between the two live-action movies? Or how Parasyte’s anime debuted the same month as its first live-action film, despite being two decades since the source manga had ended? Or how Erased’s anime, novel, and live-action film all hit during the same month that the original manga concluded?

This is because Japan, as a nation, are masters of what they call the “media mix”, a phrase that they were throwing around quite a lot well before “transmedia” became a hot buzzword in Hollywood. The notion is that you can capture an audience not entirely inclined towards your primary medium by drumming up interest in their medium of choice. In short, you can make something like an anime, drama miniseries, or video game essentially as a long advertisement for your blockbuster manga or movie property, or occasionally vice-versa.

While manga can be big business, it’s also comparably much cheaper to produce than a major motion picture, which is why in cases where the manga is not already the format of the source material, it might behoove a studio to cross-promote their upcoming film with a manga adaptation. It’s such a common occurrence that there’s even a special denomination for such novelizations: “comicalize” (コミカライズ), one of those quirky wasei-eigo terms that Japanese people often don’t realize isn’t actually used in English. There are copious examples of Japanese movies being given such treatment over the decades, sometimes from major artists in the industry. Here are some J-horror examples to keep with this month’s Halloween theme:

It’s not just domestic entertainment that gets this treatment, however; Japan also has a tradition of comicalizing Hollywood cinema. These adaptations are often viewed as disposable shorts, rarely if ever reprinted in their native country and almost never translated into English, which I think is quite a shame, especially for these titles that originate with English-language movies. So, for this Halloween, I think it might be worth diving into the strange, oft-forgotten second life some of these American movies had in the pages of Japanese manga anthologies. Due to the scarcity of some (most) of these titles, much of this will be cobbled together from various images others have posted on social media in the past, so apologies that image quality won’t be very consistent.

Kicking things off, 1973’s The Exorcist is obviously one of the most influential horror films of all time, inspiring countless imitators around the globe. In Japan, particularly, it hit at the right time to be a major catalyst in the country’s “occult boom”, when there was a huge interest in the paranormal; for example, it was off of The Exorcist’s success that the Japanese blockbuster The Prophecies of Nostradamus got greenlit, and it is also widely speculated to be the impetus for Daijiro Morohoshi’s classic Yokai Hunter manga. For such a momentous film, it’s appropriate to go to the best in the business to adapt it, and thus, the legendary Kazuo Umezz himself made an adaptation of The Exorcist for Shonen Magazine #23 in 1974. The end result is interesting and atypical for what you’d expect from a manga: it’s full color, composed of both Umezz’s hand-drawn art and promotional stills from the film overlayed; sort of half comic, half film comic. Additionally, several of the stills are black-and-white and have only been tinted to color, so it clashes with Umezz’s lush artwork. Why it would have been done this way is unclear, but it really hammers home the message that this is an upcoming live-action movie, lest the audience get confused and think of it as only a spooky manga story.

Umezz wasn’t the only titan of the horror manga field to tackle The Exorcist, however; in the August issue of monthly Shonen Champion, Shinichi Koga took a much more traditional black-and-white manga approach to adapting the story. Koga’s grotesquely contorted figures and moody crosshatched linework frankly give Umezz a run for his money, demonstrating an obvious influence on current-day horror comic wunderkind Junji Ito as well. It’s quite fitting that Koga did this one, as The Exorcist was an immense stimulus for his magnum opus Eko Eko Azarak, which he began serialization on the following year. It’s always fascinating to compare different artists taking on the exact same story, and while one could imagine a modern studio panicking over the prospect of exclusive contracts and market dilution, at the time it was not uncommon to see multiple anthologies adapt the same story in service of marketing a film to the widest possible audience, rather than viewing them as competition (e.g., Mitsuru Miura shonen adaptation of House vs Masako Watanabe’s shojo version, or how Masaru Irago and Mitsuru Hiruta were both putting out TV-accurate manga versions of Devilman while Go Nagai’s manga went off the rails).

Just two months after adapting The Exorcist, Koga was back in the pages of Champion, this time teaming with fellow horror artist Shinji Hama to do a 40-page adaptation of the US/UK coproduction The Legend of Hell House (five pages more than The Exorcist got!). Again, the style oozes atmosphere, a portent of the kind of imagery Koga would bring to Eko Eko Azarak shortly thereafter, though based on the credits it seems Koga drafted the layouts while Hama did more of the heavy lifting on the artwork itself.

If it seems an odd coincidence that both of those movies were adapted in the pages of monthly and Bessatsu Shonen Champion, it’s not just that the publisher had a proclivity for supernatural horror (at least not just that, since Eko Eko Azarak *did* begin running in Weekly Shonen Champion in 1975). Instead, they were all part of an ongoing series titled Gekiga Roadshow (“gekiga” being a more “mature” term than the light, juvenile “manga” rarely in use anymore (think “graphic novel” vs “comic”), while “roadshow” is a loan word referring to theatrical releases). The series began in 1971 with Daiji Kazumine’s adaptation of Godzilla vs. Hedorah and went for a whopping 54 monthly installments, tackling whatever the blockbuster du jour was, ranging from comedies to disaster pictures to martial arts flicks to westerns to thrillers, covering both domestic and foreign films. Naturally, this includes horror flicks, accounting for quite a number of the titles we’ll look at here.

The Exorcist and Legend of Hell House were both influences on 1976’s The Omen, so it’s fitting that that film also got an adaption, in Champion’s November 1976 issue, and although Eko Eko Azarak did have a chapter referencing the film, Koga was not involved. This time the artist was Setsuo Tanabe, a prolific comicalizer who took on a whopping eleven films for the Gekiga Roadshow, including Enter the Dragon and The Towering Inferno. The manga manages to preserve the film’s ominous (no pun intended) tone, with heavy use of black ink, gory death scenes, and a version of devil-child Damian who exudes pure malice. Plus, not a bad representation of Gregory Peck!

The Omen wasn’t the only “creepy kid” flick to arrive on Champion’s pages, but the other entries might surprise. The era had a miniature wave of such cinematic content (Rosemary’s Baby, Village of the Damned, To the Devil a Daughter), but surprisingly the independent Larry Cohen flick It’s Alive not only got a wide release in Japan, but also got adapted into a whopping 50-page manga adaptation by Yoshisato Takayama (AKA Yoshinori Takayama, who also adapted Prophecies of Nostradamus) in the November 1974 issue. While the adaptation itself appears to be (from available pages) a fairly faithful recreation of the contents of the film, it’s interesting that the preview image used to advertise the manga instead shows a relatively-normal smirking blonde child looming over stabbed bodies (as opposed to the deformed mutant baby who kills people bare-handed), which makes one wonder if the editorial department only had the title (Akuma no Akachan, “Devil’s Baby”) to work with at the time. The mutant baby does appear in the manga proper, but perhaps it could also be considered a spoiler to reveal before the climax.

(While on the “killer kids” topic, it’s also worth pointing out that June 1977’s issue of Champion had an adaptation of Who Can Kill a Child? by Gosaku Ota, one of Go Nagai’s acolytes. However, that movie is Spanish rather than American, so we won’t dwell on it here.)

I’ve spoken in the past about the Jurassic Park manga adaptation, but that’s not the only movie based on a Michael Crichton story about a theme park out of control to be comicalized. Westworld got the 41-page treatment in the January 1974 issue of Champion, and Mitsuru Hiruta did a fine job with a suitably creepy depiction of Yul Briner’s iconic killer robot cowboy proto-slasher. Combat between life and artificial life could be a halmark of Hiruta’s career, come to think of it, since he’d previously adapted Kikaider and Kikaider 01, and later the same year would give us the Gekiga Roadshow version of Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla.

Side note: Westworld also comes up in prologue to the story “Robot Land” from Astro Boy volume 4.

Not all horror has to be done with a straight face, however, as Kunio Nagatani, one of the pioneers of parody manga known for contributing to Fujio Fujiko titles like Osomatsu-kun, was tasked in the October 1975 issue of Champion with adapting Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein. Given that only a few pages have surfaced online in pretty miserable quality, plus translating comedy is a nightmare at the best of times, it’s a bit difficult to gauge, but it certainly seems that Nagatani is delivering his own spin, rather than trying to stick close to the original script; a wise decision in this adaptation.

(Gekiga Roadshow also later did Blazing Saddles, by the way, since Mel Brooks’ movies arrived in Japan out-of-order.)

Just in case I gave the misimpression earlier that The Exorcist was the biggest horror hit of the 1970s, we should clarify that there was another title that blew it (and everyone else) out of the water, in some cases literally. 1975’s Jaws changed the cinematic landscape and gave birth to the modern blockbuster, and as such has had quite an impact on Japanese cinema as well, inspiring both classics like Obayashi’s House and duds like Jaws in Japan. Naturally Champion was all over it, so the December 1975 issue featured a 50-page manga adaptation by Setsuo Tanabe, with adequate action and drama conveyed.

This is notably not the most famous manga adaptation of Jaws, however, since that was done by Herald Books, written by shojo mangaka Akira Ichijo and drawn by Sakuma Chu, clocking in at just over 100 pages. In addition to its status as a collectors’ item, this version has some nice color artwork and really ups the gekiga-factor by extending the skinny-dipping sequence at the start, even launching the woman out of the water so the reader can get a really good look at her breasts! Generally, this seems the favored manga incarnation by Jaws fans, with even more over-the-top stylization, though part of that popularity may be the difficulty in actually discovering the Tanabe version exists at all.

Of course, Jaws inspired a host of cinematic imitators, and many of those found their way onto the comics pages as well. Peter Benchley’s follow-up novel to Jaws, The Deep, was turned into a movie, and Gosaku Ota adapted it for the August 1977 issue of Champion. The month prior, future Ultraman comic artist Shinji Imura did an adaptation of Tentacles, and that wasn’t even his first Jaws-ploitation piece, since he’d also adapted The Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds for the magazine that May. January 1978 saw Kyuuta Ishikawa (Gao, Monster Prince) adapt Orca for 40 pages.

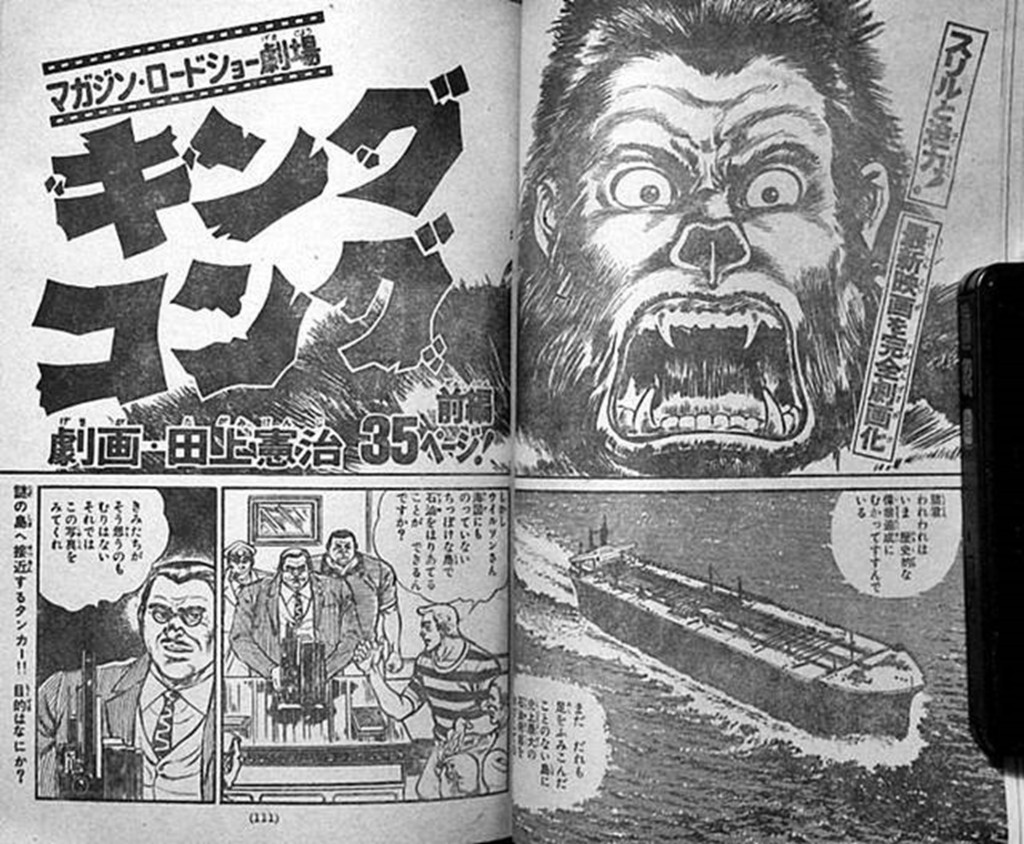

And lest we forget, the 1976 King Kong was also made in direct response to the success of Jaws. Though Japan was one of the few nations to sit out of the rush to deliver their own cinematic take on the giant ape to capitalize (unlike Italy, South Korea, the UK, and Hong Kong), it did take on the Eighth Wonder himself in both the form of video games and manga. Naturally, there was an adaptation, going above and beyond by stretching across two issues of monthly Shonen Magazine (October and November), adapted by Kenji Tagami. Tagami’s style is overly “gekiga”, trying so hard to look realistic that Dwan’s pronounced nose, chin, and muscle tone look a bit too masculine to readers accustomed to modern manga aesthetics. Kong, on the other hand, kind of looks like a man whose nose has been cut off.

However, Daiji Kazumine, the prolific kaiju mangaka who’d already taken on Kong a decade prior, also had an adaptation, as a whopping 64-pager in the December 1976 issue #51 of TeleviLand. As is fitting with the more juvenile target audience of TeleviLand, Kazumine’s Kong is a lot more friendly and cartoonier, at times looking as afraid of Dwan as she is of him, and even gives her a bouquet of flowers as he’s dying! On the other hand, he takes out a jet fighter with his teeth, which is more like something from the poster than from the actual film.

While we’re at it, we can throw Giant Spider Invasion in with other 1970s “animal panic” movies. Setsuo Tanabe did a 40-page adaptation for the September 1976 issue of Champion. Since the actual film is pretty hokey, there’s a good chance kids who went to the cinema based on the manga were let down. I do like the was Tanabe draws the sheriff character, though.

The Gekiga Roadshow series ended in the late 1970s, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, though some have speculated that Japan reprinting American-made comic adaptations of titles like Star Wars and Alien didn’t help the matter (slapping “Leiji Matsumoto Presents” on the cover of Archie Goodwin and Walter Simonson’s Alien wasn’t going to fool anyone, but they sure tried it!), effectively taking wind out from the brand’s sails by causing them to miss a few mega-blockbusters.

However, in a nation as comic-ravenous as Japan, it wasn’t long before other publication began to pick up the comicalizing slack, and as far as horror goes, the baton definitely passed not to another shonen anthology, but a shojo one: monthly Halloween. While mostly known in English-language circles as the anthology that gave us Junji Ito, Halloween was a lot more than that, basically kicking off a whole boom for female-targeted horror manga that continues to this day, although the mid-80s to mid-90s was truly the high point, with numerous anthologies like Horror House, Suspiria, Night Zone, Solitaire, Prom Night, Pandora, Mystery Bonita, and Horror M rising and falling in Halloween’s wake.

Both Ceiling Gallery and Zimmerit have great overviews on the magazine in general, so here we’ll just focus on the topic at hand: the magazine was also movie-crazy, with some issues featuring original photo shoots of iconic horror movie characters on the covers (at least, before the covers transitioned from photos to manga art towards the end of its run). Naturally, there were comicalizations of horror flicks within the anthology’s pages as well, both of Japanese titles (such as Sweet Home and Monster Heaven: Ghost Hero) and imports.

One thing that’s interesting is that three of the movies chosen to adapt are of the zombie genre; despite being the nation that reinvigorated worldwide interest in the creatures with Resident Evil in the late 90s, they were actually pretty slow to adopt the monsters. Japan didn’t get theatrical releases for a lot of the foundational zombie cinema (e.g., I Walk with a Zombie, Night of the Living Dead, Plan 9 from Outer Space), didn’t have a proper zombie feature of their own until Battle Girl in 1991 (little pieces like Youjo Melon and Legend of Stardust Brothers not withstanding). Their real breakout exposure with the genre was Romero’s 1978 classic Dawn of the Dead, which while a hit, was advertised with the zombies making the laughing noises of the mushroom people from Matango, since that was pretty much the closest frame of references audiences at the time had.

Over the next decade, though, an avalanche of foreign zombie flicks poured in, and Japanese audiences lapped them up. Now, having not actually gotten Night of the Living Dead, it makes sense that Return of the Living Dead would be retitled, in this case to Battalion (origin of the portmanteau “obattalion” for punky old ladies). Anyway, the movie got adapted in the March 1986 issue of Halloween, one of two movies that got the treatment that month (the other being Ai no Kagero). Artist Mari Eran lends the story a sketchy, cartoony style over the 50 pages, including some surprisingly faithful touches, such as the plot point about Night of the Living Dead in the backstory, and, most notably, Trash’s copious nudity, including more pubic hair than one would expect in a shojo manga. Trash actually bookends the entire work, as she’s the focus of the first panel, and the final is a cliffhanger from the scene where she’s revived as a zombie (which is also on the manga’s cover page). Perhaps due to this aspect, it’s actually quite easy to find this manga, in its entirety, uploaded to hentai sites.

Mockbuster-style exploitation is a big thing in Japanese movie marketing, but surprisingly, “…of the Dead” didn’t really take off as a title phrase there like it did in the States (at least, not until a certain Zack Snyder remake). As mentioned before, Night of the Living Dead didn’t get released there for a long time, Dawn of the Dead was released under the Italian title Zombie, Return of the Living Dead was Battalion, so when it came time to release Day of the Dead, the title took its format not from the Romero side, but from the Japanese title of Evil Dead. That movie was released in Japan as Shiryō no Harawata (“Ghost Guts”, ironically itself a play on the Japanese Angel Guts series), and its popularity inspired a wave of imitators, such as the Japanese Shiryō no Wana (Evil Dead Trap), but also a glut of western horror movies that copied the format by starting with “Shiryo no” for their Japanese titles: Silver Bullet, Deadly Blessing, The Boogeyman, Dementia 13, The Beyond, Brain Dead…the list goes on. So, Day of the Dead became Shiryō no Ejiki (“Ghost’s Victim”, or perhaps “Evil Dead Victim”).

Anyway, regardless of its title, Day of the Dead got an adaptation in the May 1986 issue of Halloween, courtesy of Yutaka Abe, one of Gosho Aoyama’s assistants on Detective Conan. The art in this version is great, and Abe takes some shojo-styled liberties here and there, such as having a somewhat touching scene between Bub and Sarah where you really ramp up the sympathy for the main zombie. The short actually did get reprinted as a bonus in the first volume of Triangle High School, so it’s a bit easier to come by than some of the ones that only printed in magazine format.

Abe followed this up with another “shiryo” comicalization, again unrelated to the prior: Shiryō no Shitatari (“Trickling of Ghosts”), AKA Zombio, or, as we call it stateside, ReAnimator. This was a particularly interesting read for me, since:

- It’s on the long side at 70 pages (40 pages in Halloween’s March 1987 issue, 30 pages in April).

- It’s somewhat easily available; it was retitled Deadly Night and reprinted in the second volume of Triangle High School.

- I’m pretty familiar with different edits and the shooting script for the source movie.

Often, novelizations can be based on earlier versions of scripts that don’t make it into the theatrical version of a film, but this follows the theatrical version of the film quite closely, which makes sense for a completed foreign movie that’s being imported. I have to wonder if Abe had an early release of the film on video for reference, or if he just had the translated script for the subtitled edition (which wouldn’t have had elements from the shooting script that didn’t make the theatrical cut) and some promotional photos. It’s easy to postulate that the brevity of the cat sequence in this adaptation, or the lack of nudity in the finale, was due to pacing for page count or toning things down for a shojo audience, but I also have to wonder how much of that could simply be that the script didn’t stress those elements because they’re so visual. Barbara Crampton’s nudity did feature quite heavily on the movie’s Japanese poster, though, so even if Abe somehow delivered the manga without the movie in hand, it’d be difficult to miss. It raises a question about the production methods of all of these adaptations, frankly.

Likely to avoid confusion with the Obayashi movie of the same name, Steve Miner’s 1986 haunted house flick House was retitled in Japan to Goblin, though the katakana rendering is closer to “gabalin” (ガバリン), perhaps to evoke the word “javelin”? The film actually did get a sizable push in Japan, with the soundtrack, a novelization, and a puzzle game book unique to the country. Naturally, this also included a manga adaptation, though it’s been a bit buried to time; unlike the other titles in this article, I couldn’t find any images from it online and I only found out it existed by scrolling through tables of contents from Halloween back issues and noticing that July 1986 (which has a House cover) also has a manga for it.

I ordered a copy, and it turns out that author Rururu Araragi took a really interesting approach to the adaptation: while the movie plays out as a series of vignettes, the manga is actually a choose-your-own adventure format. For example, when there’s a knock at the door, you can turn to one page if it’s the protagonist Roger’s ex-wife, or a different page if it’s his sexy neighbor. All the main set pieces from the film are represented, but this interactive approach to the storytelling really accentuates the bewilderment that Roger would have when dealing with the haunting.

Speaking of movies getting their characters guest spots on the cover, Freddy Krueger shows up on the front of an issue from 1990, but the manga adaptation of A Nightmare on Elm Street was actually in the June 1986 issue. This one’s by So-ko Agi (an artist whose name primarily results in this title if you google her) and tells the complete story of the film in 47 pages. Key moments like the geyser of blood from the bed and the clawed hand in the bath are preserved, though the climax is a bit truncated as it’s more about Nancy praying Freddy away than dragging him into the real world. Freddy has pointed ears in several, but not all, panels here, and while such an inconsistency might be a flaw in other works, the phantasmagoric dream-logic makes such continuity less of an issue.

Speaking of supernatural slashers, Hellraiser also got an adaptation…basically. Printed in the debut issue of monthly Bears Club in March 1988, this is technically an adaptation of The Hellbound Heart, the third time Naruho Amino had adapted a Clive Barker story for manga after The Yattering and Jack and In the Hills, The Cities. However, Amino admits that translating the book to the visual medium of comics proved difficult, and thus referenced the movie version heavily; it’s all Barker’s vision either way.

The Terminator often gets forgotten as an 80s slasher, but his debut film really fits into that mold. Tomo’o Kimura (just prior to hitting big with Let’s Dachiko) did a short comic for the movie pamphlet, emulating American comics in both that it’s in full color (probably easy enough due to its brevity), and using English-language sounds effects. Predating the NOW Comics run by a few years, this manga is actually Terminator’s debut in comic format, a claim shared by a few other characters we’ve looked at today, such as Herbert West and Freddy Krueger, whose own American comics wouldn’t crop up until a few years after their respective manga incarnations.

Though only the first Terminator really counts as a horror flick before veering more heavily into action territory, it’s also worth noting that future Redline director Takeshi Koike drew the Terminator 2 T-800 in an illustration for Animage, while Terminator 3 got an entire volume-long manga adaptation by Ark Performance (Gamera: Hard Link).

While it’s not a movie, per se, I also think it’s worth mentioning that the 1983 TV miniseries V (which, incidentally, is not a particularly Google-friendly name) got a two-volume manga adaptation in 1989 by Go Nagai and Tatsuya Yasuda (drawing as Tatsuo Yasuda). This one was officially released in France and Italy, but alas, no English-language attempts yet. Reviews claim that the manga is nigh-incomprehensible if you haven’t already seen the show, but the imagery of the reptilian aliens in human disguise feels almost tailored-made to the manga format, coming across better than its live-action counterpart.

In recent years, comicalizations of western horror flicks haven’t proven quite as common as in the past, but every once in a while, there’s still an occurrence, usually from smaller studios rather than major blockbusters. One such example was even in the pages of monthly Shonen Champion, even: Kenji Hirasawa did an adaptation of the Daniel Craig/Naomi Watts thriller Dream House for the December 2012 issue. It’s a far cry from the days of Gekiga Roadshow, though, as Hirasawa’s style is quite cartoonish.

Suzuki-sensei’s Kenji Taketomi did an adaptation of Jerry Bruckheimer’s Deliver Us from Evil in 2015 to commemorate the home video release. It seems like a nice fit into the overall oeuvre of ESP media that Japan enjoys, if potentially a few decades late on the boom.

Most recently, Junji Ito did an adaptation of Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse that was available in film booklets (i.e., sold in theaters playing the movie), a nice synergy since both the mangaka and the movie skew thematically Lovecraftian. Given Ito’s incredible international popularity at the moment, it’s honestly kind of shocking that this one wasn’t brought back to the US in any official capacity. It’s drawn more realistically than Ito’s normal style, but really captures Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson in stellar interpretation.

Aside from doing comic adaptations, sometimes mangaka also get hired to do posters for Japanese releases of Western movies, often with some tenuous connection (like Monkey Punch illustrating Jackie Chan posters because he was also nicknamed Monkey, or Masami Kurumada doing Clash of the Titans because Greek mythology), so there’s no surprise that horror artists wind up tackling horror films. A few examples:

- Kazuo Umezz drew a poster for the Ghost House production The Possession, adding his trademark sound effect “gwashi” from Makoto-chan into the palm of the hand in the art

- Nori Ochazuke (Fear Infection) did two posters for Annabelle

- An unknown artist did a cover for An American Werewolf in London, really playing up the comedic appeal of the film, perhaps due to it being a John Landis project

- Five different artists did posters for Winchester

- Original Death Note artist Takeshi Obata did a poster for the Adam Wingard film adaptation

- When the 2019 Hellboy was released, Dynamic productions created a crossover poster with Devilman. Original Hellboy creator Mike Mignola reciprocated by drawing a Hellboy/Devilman crossover of his own

- While both films are European, it’s worth noting that Junji Ito did a poster for Inside and home video covers for both Demons movies

A common thread between all the manga discussed today is that none of them have been made available in English, so I’ll wrap this on a glimmer of hope with one that actually did get a US release via Tokyopop and is still easily available to buy and read. Actually, of all the titles, perhaps it’s the one most appropriate for Halloween…or maybe you’re better off saving it for Christmas instead. That’s right, The Nightmare Before Christmas was adapted by Jun Asuka at Kodansha, and she brings a suitably shojo touch to the entire affair, to the delight of goths everywhere. My main critique of Tokyopop’s release is the cover, which is quite monochromatic compared to the Japanese release, but it’s a price that must sometimes be paid. Whether you do pick up the book or not; hopefully you got something out of this article, and Happy Halloween!

Excellent places I cribbed from; scope them out for similar material: